RELEASES TOMORROW! If you have read or are reading this novel of mine, I’m so happy you stopped by. Please remember to share these blog posts and let people know that they can Preorder ALL THINGS HUGE AND HIDEOUS here. Also available IN PAPERBACK!!

RELEASES SEPTEMBER 5TH!

Part VII: Blood Test

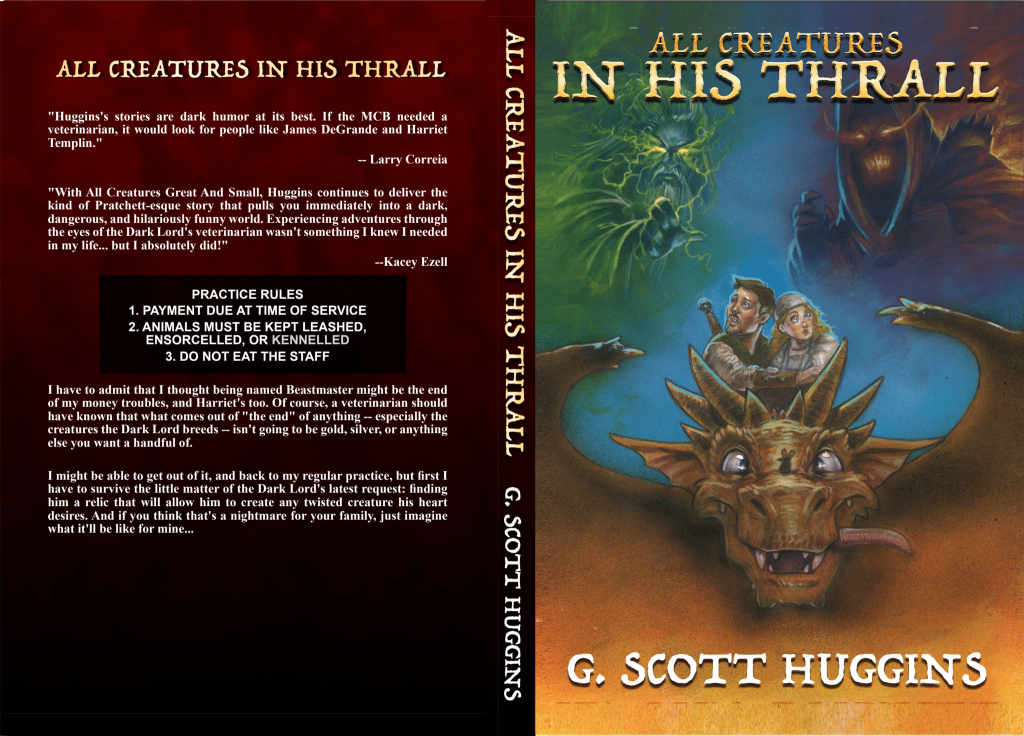

I have three rules for my clients:

Pay at the time of service.

Control your animal.

Do not abuse the staff.

If you’re going to violate these rules, you’d better know another doctor, and you’d better be able to get there faster than I can run while carrying my No. 75 dragon scalpel, because one of the tenets of my philosophy of care is that rudeness is a malignant tumor that can be effectively treated by immediate excision.

So when I heard a snarl, followed by Harriet’s scream from the front of my practice, I was out of the back and fully prepared for surgery in about three heartbeats.

Harriet was clutching the desk, trying not to move. Perched on the hump of her back was a large, vampire bat, its wings outstretched and its fangs poised to strike the back of her neck. I whirled on its owner, raising my scalpel.

And then carefully laid it down at my feet.

“The Dark Lord will see you, now,” said the tall shape in the thick black robes.

There is one other way to violate the rules I mentioned and avoid having your guts resectioned. I don’t like to talk about it. But you can also be the Prime Minister of the Dark Lord of the World.

“Minister Praxitela,” I bowed. “What an honor that you came to tell me yourself.”

“Yes, it is,” the vampire said, her voice thick with disdain and fury. “And immortal though I am, I can feel my time being wasted every second you delay. Move, human.”

I straightened. Immortality didn’t stop me from killing you last time, would have been both true and extremely unwise to say. I looked over at Harriet, who was still flinching beneath the fangs of Praxitela’s huge bat. Harriet had never really explained how she had managed to resurrect Praxitela at the Dark Lord’s command. But it looked as though the vampire lord was anything but grateful for it.

“To best serve our Lord,” I said smoothly, “I should know what animal needs to be treated.”

“If you delay me another instant,” she said. “It will be you.”

“Very well,” I said. “Harriet, we are attending upon the Dark Lord. Close up.”

“Ah, James..?” she said, through gritted teeth.

“Of course,” I said. “Without my assistant, I shall be much less use to His Great Darkness,” I said, gathering up my scalpel and carefully sheathing it.

Praxitela fixed me with a glare, and raised her finger. “Very well,” she said. The great bat flew back to her shoulder, raking Harriet’s shoulder, casually. Harriet swallowed a whimper and walked as steadily as she could to the back room to gather our things.

I’m sorry if my behavior doesn’t strike you as badass enough for your taste, but there are times to stand up for your dignity, and they are not when facing the barely-leashed ire of a vampire lord you have already killed once. They hold grudges about such things. Besides, we both knew who was ahead in the game.

“The practice is closed for the day,” I said to the crowd, most of whom were on their knees before the vampire already. Even Baron Klathraee merely rose, bowed from the neck, and left. When the dark elf lord shuts up, it’s wise to do the same.

“And perhaps longer,” Praxitela murmured.

At these words, a chill ran down my spine. Praxitela knew something that I did not. What? I had no idea. But it was important enough to get her out during daylight hours, and it wasn’t that she’d been given permission to kill me outright. If it was that, she’d have just done it, and the more witnesses, the better she’d have liked it.

Still, I knew something she didn’t, too. Trying to look casual, I reached through my office door and, using all of my strength, took the cloak of Aurmor off its reinforced hook. Harriet reappeared at my side and I saw her eyes widen as she recognized it. I felt myself lose half an inch of height as it settled on my shoulders. I hoped it would be enough to buy our freedom. And the look on Praxitela’s undead face would make it just that much sweeter.

We passed through the gates of the Dark Tower faster than I was used to. For one thing, I wasn’t allowed to use the great gates. For another, the orcs on guard usually liked to make humans wait.

Before Praxitela’s cowled shape, they dropped on their faces.

Other humans always ask me what the Dark Tower is like, and answering that question always throws me. What’s it like? You know what it’s like. A half-mile tall, sticking up out of the earth like a needle from a wound the size of a continent. Some say that’s what it is. That it’s how the Dark Lord came here. That he and his Dark Tower stabbed into our world from somewhere else. For all that it’s made of black stone, the surface glistens like an oil slick. Volcanic glass, I think, though I’ve heard people swear it’s black diamond, carved into razor-sharp edges and crenellations like claws. Each tower reaches higher than the last until the pinnacle of it disappears in the clouds beyond.

You want to know what it’s like inside, though, don’t you?

Trust me, you really don’t.

Oh, on the most basic level, it’s perfectly straightforward: the interior walls are just like the exterior. The Dark Lord likes bare stone and dark metal. Or he doesn’t care enough to cover them. But there’s too much inside the Tower that no one ought to see.

I could tell you about the hallways that curve off in directions that shouldn’t be there. I could tell you about some of the windows – just some of them – that do not open onto the city that we think of as below the Dark Tower. But there’s a lot more than how it looks to worry about. There are the echoes that you hope you never see the source of. There’s the way the air hangs perfectly still until a chill breeze hits you and cuts right through anything you happen to be wearing. It passed through the Aurmor cloak like it was gauze. And there are the smells they carry. I would tell you not to eat before you go into the Dark Tower, but it’s not as though you’re likely to have a choice of when you go if you’re summoned to dinner. And you’re not likely to be the diner, either.

All that, and I haven’t even touched upon what you’ll meet in the halls.

Even if I’d been afraid of what Praxitela would do to me, I wouldn’t have run away from her in the Dark Tower. My chances of ever coming out again would be nil.

Harriet stumbled against me and I remembered with a thrill of dread that it was her first time. I closed my hand on what was supposed to be her shoulder, and ended up being the curve of her spine. “Do not vomit in here,” Guilt and fear made my voice harsher than I’d intended, and she pulled away, glaring at me. But she swallowed hard and her pace steadied.

We were taken directly to the Room. With any other ruler, it would be a throne room. But the Dark Lord doesn’t sit. He just is.

He looked the way he always looks. Taller than any man, cloaked and hooded in shadow and crowned with black iron. Tendrils of night flowed from him, hiding the floor. Is it really made of bones? I couldn’t tell you, but it’s not smooth.

DR. JAMES DEGRANDE.

I dropped to my knees before him and bowed my head. Harriet did the same. I waited to hear my assignment.

YOU ARE TO BE ELEVATED TO THE OUTER COUNCIL, TO TAKE UP THE POSITION OF BEASTMASTER.

What?

AURANGAZEB HAS BEEN EATEN. WE BELIEVE HE HAS BEEN CARELESS. WE TRUST YOU WILL BE MORE CAREFUL.

I blinked. But I was still in the Room, and night still swirled around my fingers. I was not having a nightmare.

“James…” Harriet’s voice was a rising whimper.

“Yes, Lord,” I babbled. “You do me too much honor.” Far, far too much.

INDEED. PRAXITELA WILL EXAMINE YOU. MINISTER, YOU MAY EXAMINE THE DOCTOR IN ANY WAY THAT TESTS HIS SUITABILITY TO PERFORM THE DUTIES OF HIS NEW POSITION AND TO FACE ITS RISKS, USING THE RESOURCES AVAILABLE TO HIM. NO MORE. SERVE WELL, AND LIVE.

I was dead. Praxitela, as my examiner? She rose. So did I. I caught my breath, clutching my last chance for life and more.

“Great Lord of Darkness, I beg you to hear your slave’s plea.”

Praxitela hissed. There was an endless moment of silence. I didn’t dare raise my eyes.

SPEAK, DR. DEGRANDE.

“With your permission, Great Lord, I wish to buy my freedom.”

Only my heart beat in that moment.

AND WHAT HAVE YOU TO OFFER FOR THAT WHICH HUMANS FOOLISHLY PRIZE ABOVE ALL ELSE?

Slowly, I undid the clasps that held the cloak on my shoulders. It fell as if sucked down to the floor. I heaved it up and ripped it open, showing the golden scales. “This cloak of Aurmor, Lord. Given me for services rendered.”

For once, I had the pleasure of seeing Praxitela truly shocked. Her face was frozen, but her red eyes darted from me, to the cloak, and back again.

FOR SERVICES RENDERED. AND WHAT SERVICE DID YOU RENDER, DR. DEGRANDE, THAT WAS WORTH THE RANSOM OF A HIGH NOBLE?

I had expected this question, but had nothing to fear from it. “I killed an enemy of yours, Great Lord, when he attempted to bribe me into conspiring with him to bring about your downfall. Afterward, he no longer needed it.” And every word of that was the truth.

RESOURCEFUL, DR. DEGRANDE, the Dark Lord said at last. TOO RESOURCEFUL TO LOSE AS AN ASSET. I DO NOT ACCEPT YOUR PRICE. I HAVE ALL THE MAGICAL ARMORS I COULD WANT. I NEED NO MORE.

The Aurmor hung in my grasp, weightless in comparison to my disappointment.

NOW GO, AND BE INDUCTED INTO YOUR NEW POSITION.