Last week, my retro review on the film No Country For Old Men got a fair amount of commentary from people (for my blog, anyway), from people who liked the film. One friend of mine said that he found its deconstruction and defiance of tropes refreshing.

Of course, it shouldn’t be necessary (but I admit that it is) to say that anyone can like anything, for any reason. We all have films we “just like” no matter what, either because we think they’re objectively better than most people do, and can defend that on some level, or they just tickle our “cool” centers in all the right ways. And if No Country For Old Men is to your taste, then far be it from me to say you can’t or shouldn’t like it.

But I do challenge the defense of the film on the grounds that it defies conventions. Nothing is good or interesting JUST because it “defies” anything. A raw onion sundae would “defy” the tropes and conventions of dessert. That doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

For too long, critics and authors who would claim the avant-garde position have used the term “deconstruction” as a defense for works that ignore or leave out major elements of storytelling, and use it to praise them as somehow being wonderfully creative or bold. And I’m sorry, but it’s past time for someone to say that The Emperor Has No Clothes. And I find that analogy strictly accurate. The Emperor’s problem wasn’t that he said, “Hey, everyone, I’ve decided that nudity is the way to go!” No, the problem was that he insisted that everyone admire his “new clothes” and threatened to call them fools if they refused and spoke the truth.

In the same way, works like No Country For Old Men provides less than a traditional story and their writers and admirers insist that they are more. That they are somehow “more real” or “more authentic” than a “traditional narrative” because it lacks what that narrative provides: structure, conflict and resolution. It’s like Raw Food fanatics who don’t cook and insist that they are superior for refusing to. And those are all the marks of a fad, not of penetrating insight.

Now, does that mean that deconstruction is always bad? Of course not. Especially as a writing exercise, it can be very good, because it can point readers and writers to fresh understandings of how and why stories work. Just like tasting raw foods can help people become better cooks and appreciate a wider variety of tastes. But acknowledging and using that fact is very different from plopping some artistically-arranged crudité on someone’s plate and telling them it’s better or more “authentic” because it defies the tropes of cooking.

And yes, of course “traditional narratives” can get old, tired and overdone. But that doesn’t mean that they are automatically old, tired and overdone simply by adhering to conventions of structure, any more than cooking or clothing can become passe by applying heat to food or cloth to bodies. In fact, what is more likely is that the “challenges” to these structures will become passe even more quickly, because they are by definition less complex and more reliant on a single factor to please their audience: the “defiance” of convention. They have little or nothing else to recommend them.

And when these avant-garde, deconstructionist, “challenging” scripts are themselves, in the normal course of things, challenged, too many of their admirers defend them by essentially saying, “If you don’t like it, you’re just too stupid and unsophisticated.” That this is not even an argument, let alone a good one, should hardly need to be stated. And if it is to be contended that the man who can appreciate more tastes is more sophisticated than the man who can appreciate fewer, the limits should be obvious. Certainly, a man who can only eat chicken nuggets and macaroni and cheese is no better than a five year-old child. A man who can appreciate lobster, caviar, and balut is likely a passable gourmand. But a man who can appreciate eating wood-shavings and moldy tomatoes is at least flirting with insanity.

Finally, I reject the contention that deconstruction or defiance is necessary to engage with the full range of human experience. Certainly, there is value in pessimistic themes, such as memento mori, or the idea that fate will work against the righteous and support the evildoer. But as I pointed out previously, that was being done as long ago as Oedipus Rex and arguably, Gilgamesh. In fact, Llewellyn Moss’s character in No Country For Old Men bears some resemblance to Gilgamesh: a “hero” who essentially wants to steal happiness and yet finds out that he can’t because fate will not allow it. Therefore it is disingenuous — and in fact objectively false — to argue that the expressions of such themes are somehow objectively “new and refreshing.” In fact, it is just another well-known trope with “the gods” and “fate” filed off and replaced by labels saying “chaos” and “real life.” It is, as I said, Satanas ex machina, with the writers taking the side of the villains rather than the heroes.

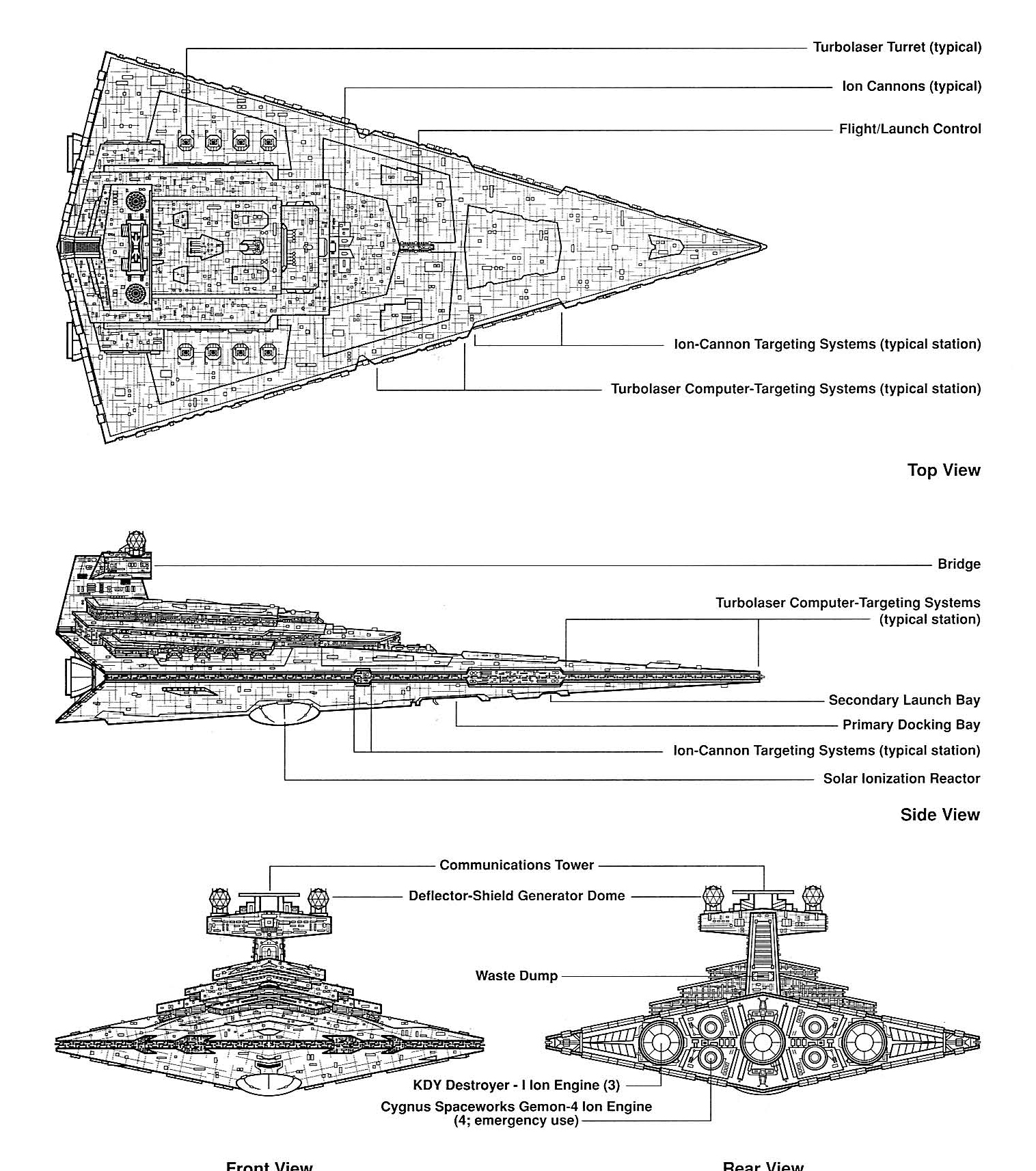

Furthermore, were we to hold the sequence of events laid out in No Country For Old Men up to a mirror, with the heroes in the place of the villains, with Chigurh running stupidly after Moss but being thwarted at every turn by the power of the hero’s… well, purity and righteousness (since the only explanation we ever get as to how Chigurh can vanish in the middle of gunfights, and appear noiselessly behind ex-special-forces officers is that he’s a relentless psychopath), the story you’d get would be somewhere between the fantasies concocted by my 9-year old (in which the Rebel Alliance has 5 Death Stars and destroys the Empire with contemptuous ease) and bad anime, where the heroes laugh/sneer at the bad guys while kicking their ass. And people would justly say, that it is puerile and simplistic. But somehow, when nihilism and brutality are held up as the bestowers of supremacy, rather than faith and chivalry, we are to believe it is thoughtful and sophisticated.

And this is simply wrongheaded. It is false sophistication, similar to the college student who sneers at his middle-school brother for slurping down strawberry soda while extolling black coffee and chugging Budweiser. It’s saying, “Look how grown-up I am!” It says more about the critic than it does about the film when what is NOT there, (character motivation, backstory, plot structure) is held up as a virtue. It’s not a virtue. It’s actually less. And it can be a very well-acted/directed “less,” (which I will stipulate that No Country For Old Men is) just as bad anime or science-fiction can LOOK awesome. And of course, it’s possible for that to be more enjoyable. There’s LOTS of “traditional narrative” films worse than No Country For Old Men, just as I’ve had lots of “apple pies” that have tasted worse than a really good raw apple. But a true judgment will be found in comparing the best of both.