Okay, it’s time to discuss one of my favorite topics: Pet Peeves Of Science-Fiction. In this edition, we’ll discuss really awful naval architecture.

Naval architecture is, of course, the science and art of designing warships. Now, for most of history, warships were really just floating fighting platforms that rammed into each other, after which the soldiers aboard tried to kill one another in various awful ways. With the advent of guns, people had to decide where to put them, and the physics of sailing pretty much meant that the guns, which were very small compared to the ship, had to be placed in broadsides, like so:

However, with the advent of better steel and larger guns, cannon could be built that were a significant fraction of the ship’s width, and launch shells that would gain a lot from being able to elevate the guns significantly. Additionally, these guns were too heavy to permit the ship to carry twice as many of them that would be permanently pointed away from the ship. With the simultaneous elimination of sail, that meant that guns could and should be placed in turrets with about 270 degrees of action, thus:

Of course, 360 degrees of action would have been better, but you have to have a place for the bridge, the smokestacks, and of course, the OTHER GUNS to be, safely.

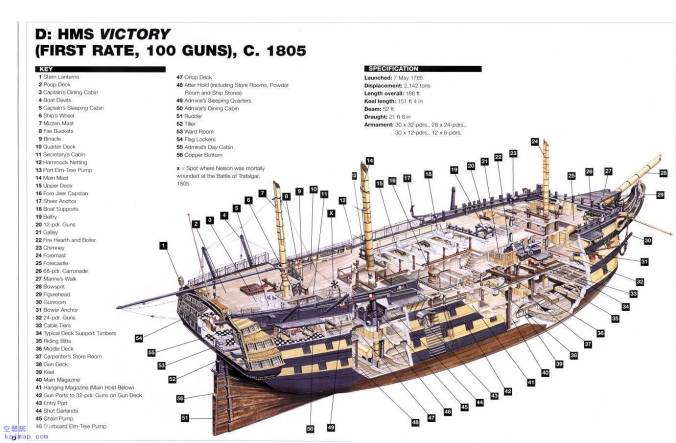

Okay, so that’s basic fields of fire as influenced by technology. Okay, ready? THIS is an Imperial Star Destroyer:

Take a good look at the turbolaser batteries. They are arranged in broadsides, and they are tiny compared to the ship, and most ridiculously, they are in turrets.

Now, the fact that they are tiny is not a problem. We know from Star Wars canon (no pun intended) that these are very powerful ships. It may be that Star Wars ships HAVE to be that much bigger than the weapons they carry simply to power them, and that most of that mass IS power generation.

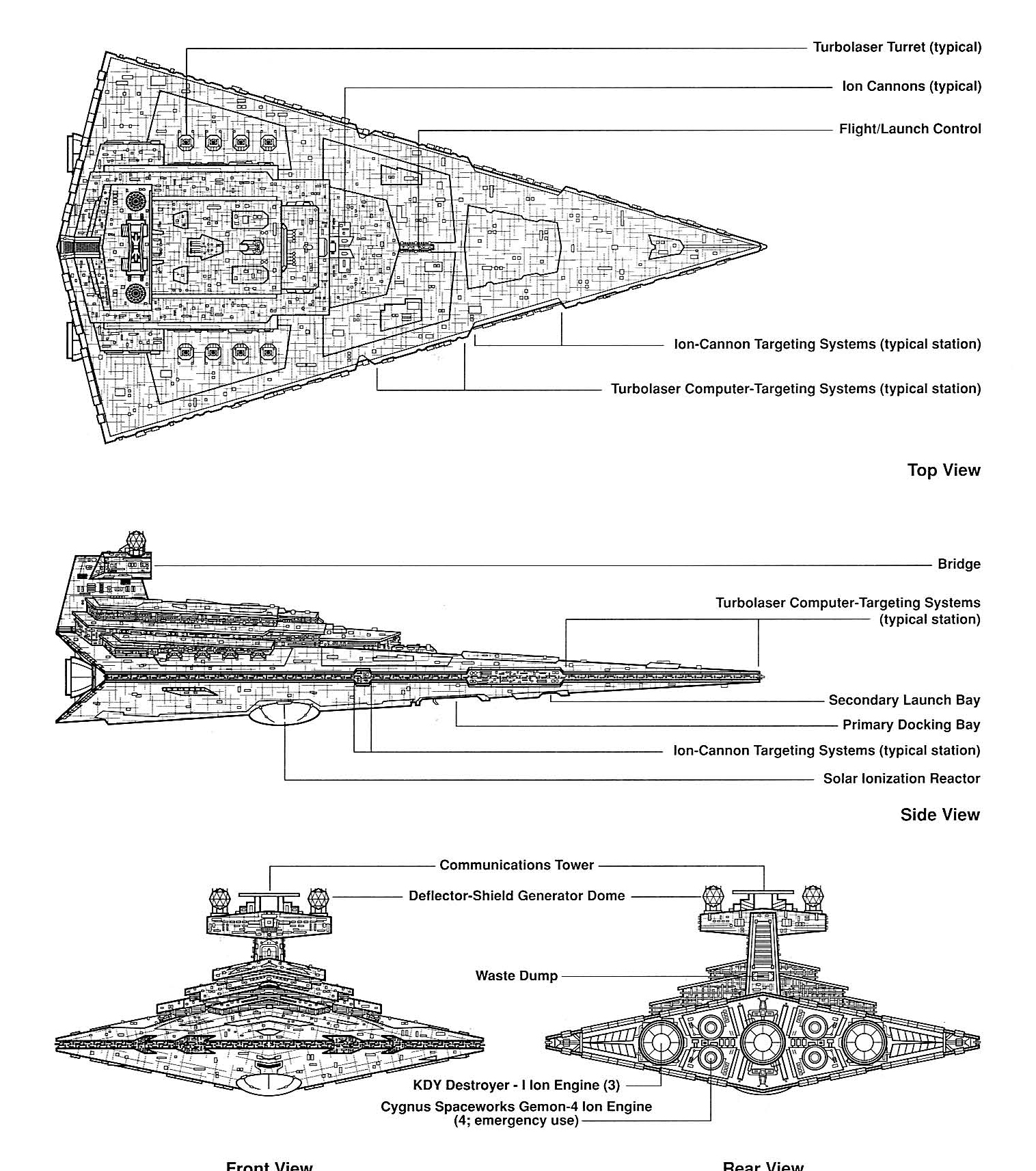

But they are arranged in broadsides, and only half of them can fire at a given moment because of the superstructure. Which begs the question: was there any reason these guns couldn’t have been put on the BOTTOM of the ship? They can’t even fire forward or aft except at half-strength, because the guns block each other. For a simplified version, they look like this (please forgive the ridiculously poor computer drawing skills):

Now in space, there’s no excuse for this., especially when we know that the Star Wars universe has the technology to make very fast and maneuverable turrets. The only way this makes sense at all is if a Star Destroyer can roll and pitch so fast that turrets don;t really matter at all, and we know from the events of pretty much all Star Wars movies that this is not the case.

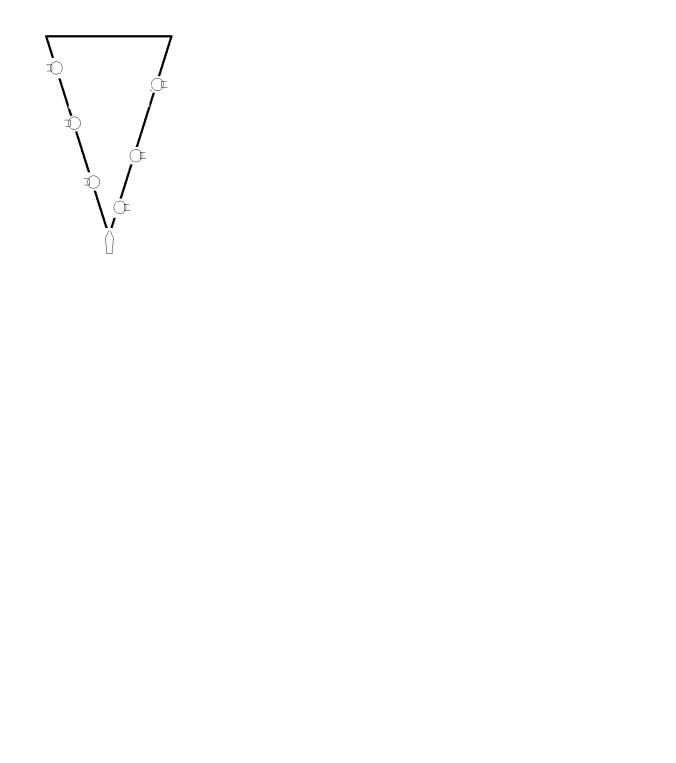

A far superior design would be this:

From this design, we can immediately see that I don’t know how to manipulate images very well, but we can ALSO see (and this is my point) that with larger, globular turrets that could clear the entire hull, a Star Destroyer design could easily have been imagined that would have allowed all turrets to bear on targets both above and below and (assuming, again, large turrets and a FLAT hull), to fore and aft, and even to both sides simultaneously by offsetting them as pictured. The bridge (assuming it could not have been buried deep in the hull, which is where it always SHOULD have been) could be moved up front.

Why isn’t this done? Well, I suspect that for one thing, people tend to find asymmetry ugly, even when it is practical. And for another, Lucas seems to have really liked the idea of big ships with tiny guns, possibly to justify his overreliance on space fighters (about which more another time). But it just annoys me when people build ships that, for no apparent reason, have huge unnecessary blind spots. When we build the ships of the future, they should at least be well-built.